IBM Cloud Code Engine is a fully managed, serverless platform that runs your containerized workloads, including web apps, micro-services, event-driven functions, or batch jobs. Code Engine even builds container images for you from your source code. Because these workloads are all hosted within the same Kubernetes infrastructure, all of them can seamlessly work together. The Code Engine experience is designed so that you can focus on writing code and not on the infrastructure that is needed to host it.

I am a big fan of Kubernetes, it is a very powerful tool to manage containerized applications. But if you only want to run a small application without exactly knowing how much traffic it will generate then Kubernetes may be too big, too expensive, and too much effort. A serverless platform would most likely be better suited for this, for example Knative Serving. But it still requires Kubernetes. If you run a Knative instance on your own you probably don’t gain much. This is where something like IBM’s Code Engine comes to play: They run the (multi-tenant) environment, you use a little part of it and in the end pay only what you use. You don’t pay for any idle infrastructure. Code Engine is currently available as a Beta.

Code Engine offers 3 different options:

- Applications

- Jobs

- Container Builds

Applications and jobs are organized in “Projects” which are based on Kubernetes namespaces and act as a kind of folder. Apps and jobs within each folder can communicate over a private network with each other.

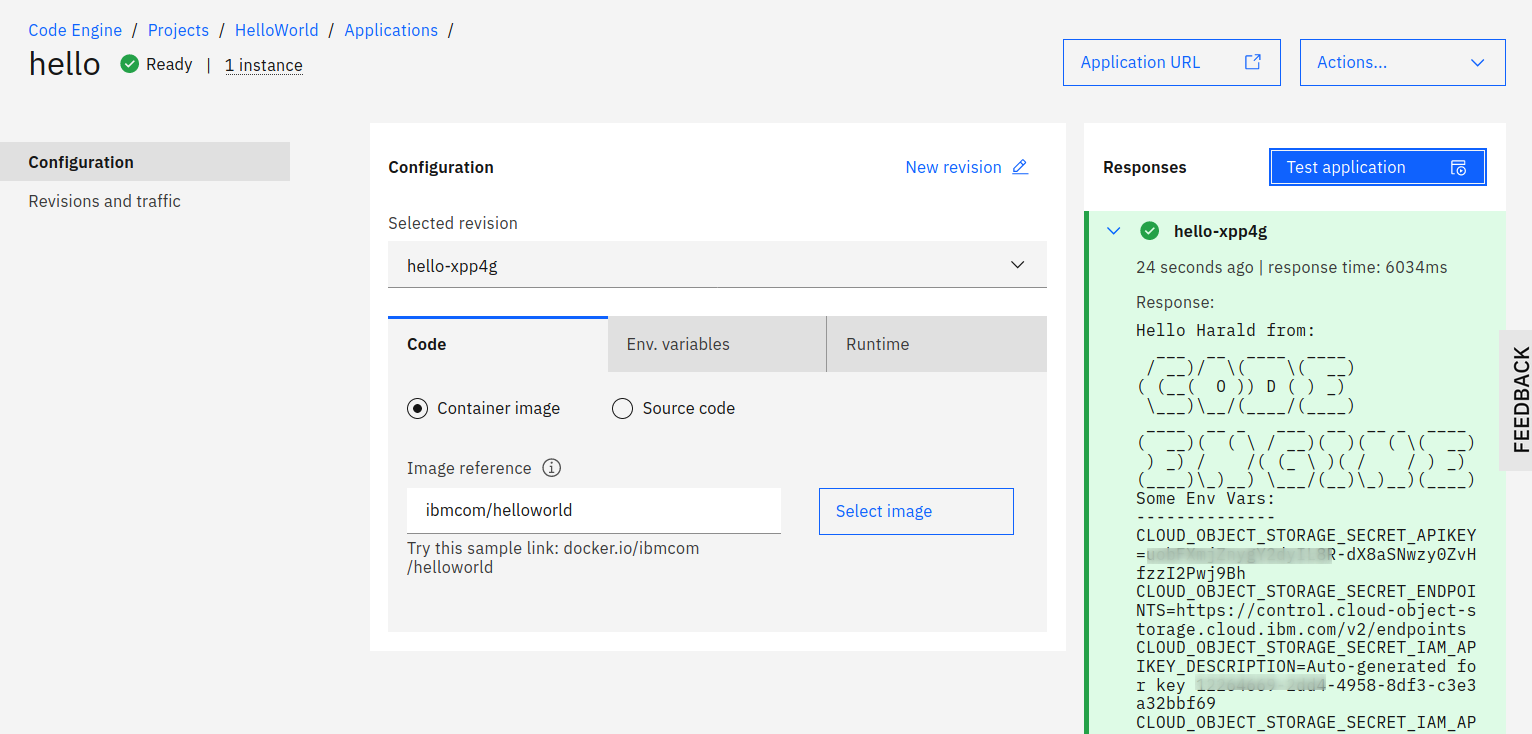

Run your code as an application

This is based on Knative Serving. A container image is deployed, it runs and accepts requests until it is terminated by the operator. An example would be a web application that users interact with or a microservice that receives requests from a user or from other microservices. Since it is based on Knative serving it allows scale-to-zero; no resources are used and hence no money is spent when nobody uses the service. If it receives a request, it spins up, serves the request, and goes dormant again after a time-out. If you allow for auto scaling, it spins up more instances if a huge number of requests come in. Knative Serving itself can do this but IBM’s Code Engine offers a nice web-based GUI for this. And some additional features that I describe later.

Run a job

What is the difference between an app and a job? An app runs until it is terminated by an operator, and it can receive requests. A job doesn’t receive requests and it runs to completion, i.e. it runs until the task it has been started for is complete. This is not Knative Serving but Kubernetes knows jobs and in the linked document is an example that computes π to 2000 places and prints it out. Which is a typical example for a job.

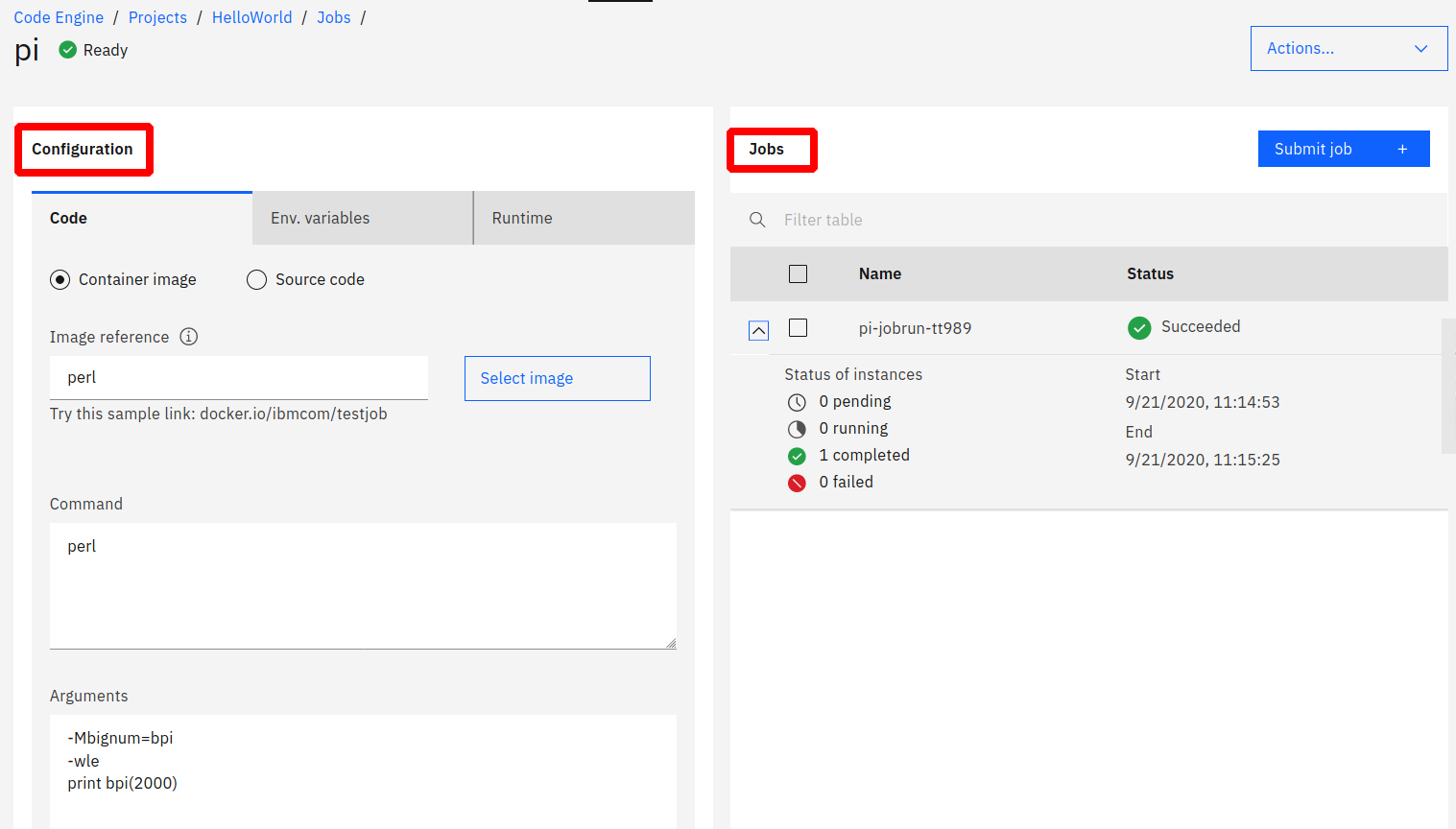

This is how the job would look in Code Engine:

There is a Job Configuration, it specifies the container image (perl) and in the Pi example the command (perl) and the 3 arguments to compute π to 2000 places and print it.

Submitting a “jobrun” creates a pod and in the pod’s log we will find π as:

3.14159265358979323846264338327950288419716939937...

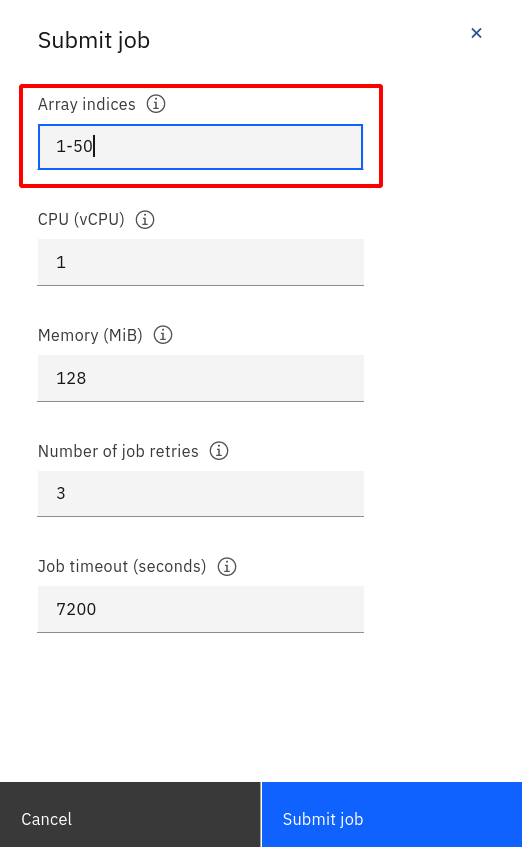

The Submit Job is interesting:

This is where a Code Engine job differs from Kubernetes: In this screenshot, Array indices of “1-50” means that Code Engine will start 50 jobs numbered 1 through 50 using the same configuration. It doesn’t really make sense to calculate the number Pi 50 fifty times. (It should render the identical result 50 times, if not, something is seriously wrong.) But imagine a scenario like this: You have a huge sample of sensor data (or images, or voice samples, etc.) that you need to process to create a ML model. Instead of starting one huge job to process all, you could start 50 or 100 or even more smaller jobs that work on subsets of the data in an “embarrassingly parallel” approach. The current limit is a maximum of 1000 job instances at the same time.

Each of the pods for one of these jobs in an array gets an environment variable JOB_INDEX injected. You could then create an algorithm where each job is able to determine which subset of data to work on based on the index number. If one of the jobs fails, e.g. JOB_INDEX=17, you could restart a single job with just this single Array index instead of rerunning all of them.

Build a Container Image

Code Engine can build container images for you. There are 2 “build strategies”: Buildpack and Dockerfile:

Buildpack (or “Cloud Native Buildpack”) is something you may know from Cloud Foundry or Heroku: the Buildpack inspects your code in a source repository, determines the language environment, and then creates a container image. This is of course limited to the supported languages and language enviroments, and it is based on a number of assumptions. So it will not always work but if it does it relieves developers from writing and maintaining Dockerfiles. The Buildpack strategy is based on Paketo, which is a Cloud Foundry project. Paketo in turn is based on Cloud Native Buildpacks which are maintained under Buildpacks.io and are a Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) sandbox project at the moment. Buildpacks are currently available for Go, Java, Node.js, PHP, and .NET Core. More will probably follow.

The Dockerfile strategy is straightforward: Specify your source repository and the name of the Dockerfile within, then start to create. It is based on Kaniko and builds the container image inside a container in the Kubernetes cluster. The Dockerfile strategy should always work, even when using Buildpack fails.

The container images are stored in an image registry, this can be Docker Hub or the IBM Cloud Container Registry (ICR) or other registries, both public and private. You can safely store the credentials to access private image registries in Code Engine. These secrets can then be used to store images after being build or to retrieve images to deploy a Code Engine app or job.

Of course, you don’t have to build your container images in Code Engine. You can use your existing DevOps toolchains to create the images and store them in a repository and Code Engine can pick them up from there. But its nice that you can build them in a simple and easy way with Code Engine.

Code Engine CLI

There is a Code Engine plugin for the ibmcloud CLI. Currently the Code Engine (CE or ce) CLI has more functionality than the web based UI in the IBM Cloud dashboard. This will most likely change when Code Engine progresses during the Beta and when it becomes generally available later.

You can use the CLI to retrieve the Kubernetes API configuration used by Code Engine. Once this has been done you can also use kubectl and the kn CLI, you do have only limited permissions in the Kubernetes cluster, though. I have made a quick test: kubectl apply -f service.yaml does work, it creates an app in Code Engine. kn service list or kn service describe hello also work. You ar enot limited to the ibmcloud CLI, then.

Networking

Code Engine apps are assigned a URL in the form https://hello.abcdefgh-1234.us-south.codeengine.appdomain.cloud. They are accessible externally using HTTPS/TLS secured by a Let’s Encrypt certificate. If you deploy a workload with multiple services/apps, maybe only one of them needs to be accessed from the Internet, e.g. the backend-for-frontend. You can limit the networking of the other services to private Code Engine internal endpoints with the CLI:

$ ibmcloud ce application create --name myapp --image ibmcom/hello --cluster-local

This is the same you would do with a label in the YAML file of a Knative service.

Code Engine jobs do not need this, they cannot be accessed externally by definition. Jobs can still make external requests, though. And they can call Code Engine apps internally, there is an example in the Code Engine sample git repo at https://github.com/IBM/CodeEngine.

Integrate IBM Cloud services

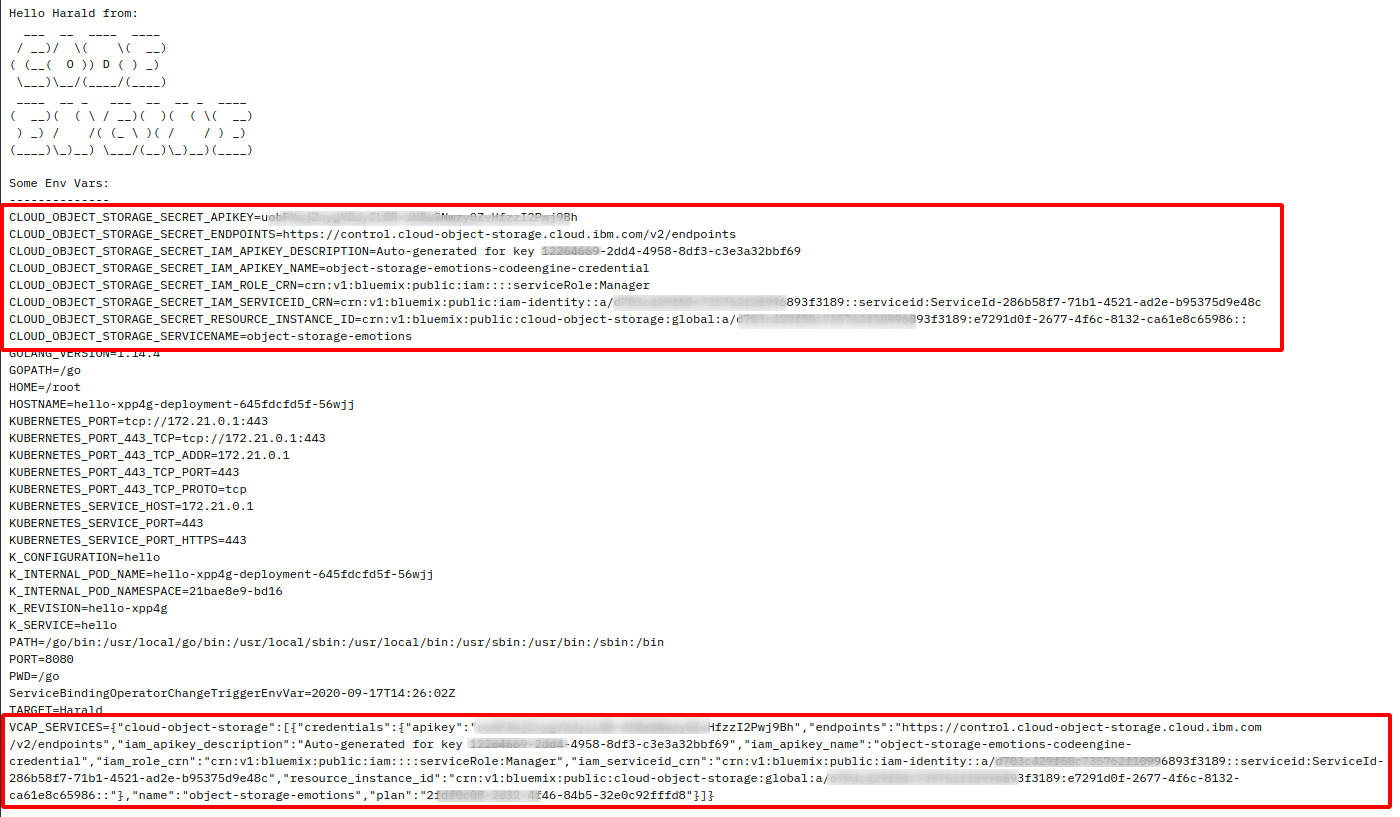

If you know Cloud Foundry on the IBM Cloud this should be familiar. IBM Cloud services like Cloud Object Storage, Cloudant database, the Watson services, etc. can be “bound” to a Cloud Foundry app. When the Cloud Foundry app is started, an environment variable VCAP_SERVICES is injected into the pod that holds a JSON object with the configuration (URLs, credentials, etc.) of the bound service/s. The application starting in the pod can then retrieve the configuration and configure access to the service/s. The developers of Code Engine have duplicated this method and in addition to the JSON object in VCAP_SERVICES they also inject individual environment variables for a service (for code that struggles with JSON like Bash scripts).

The helloworld example displays the environment variables of the pod it is running in. If you bind a IBM Cloud service to it, you can display the results with it:

This binding of IBM Cloud services is really interesting for Code Engine jobs. Remember that you cannot connect to them and they can by themselves only write to the joblog. With this feature, you can bind for example a Cloud Object Storage (COS) service to the job, place your data into a COS bucket, run an array of jobs that pick “their” data based on their JOB_INDEX number, and when done, place the results back into the COS bucket.

You may have guessed that under the covers, binding an IBM Cloud service to a Code Engine app or job creates a Kubernetes secret automatically.

Conclusion

Keep in mind that at the time of this writing IBM Cloud Code Engine has just started Beta (it was announced last week). It still has beta limitations, some functions are only available in the CLI, not in the Web UI, and during the Beta, price plans are not available yet. But it is already very promising, it is a very easy start for your small apps using serverless technologies. I am sure that there will be more features and functions in Code Engine as it progresses towards general availability.