This is part 3 of my blog series about Serverless and Knative. I covered Installing Knative on CodeReady Containers in part 1 and Knative Serving in part 2.

Knative Eventing allows to pass events from an event producer to an event consumer. Knative events follow the CloudEvents specification.

Event producers can be anything:

- “Ping” jobs that periodically send an event

- Apache CouchDB sending an event when a record is written, changed, or deleted

- Kafka Message Broker

- Github repository

- Kubernetes API Server emitting cluster events

- and many more.

An event consumer is any type of code running on Kubernetes (typically) that is callable. It can be a “classic” Kubernetes deployment and service, and of course in can be a Knative Service.

A good source to learn Knative eventing is the Knative documentation itself and the Red Hat Knative Tutorial. I think, the Red Hat tutorial is better structured and more readable.

There are three usage patterns for Knative Eventing, the first one being the simplest:

Source to Sink

In this case, the source sends a message to a sink, there is no queuing or filtering, it is a one-to-one relationship.

(c) Red Hat, Inc.

(c) Red Hat, Inc.

Knative Event Sources are Knative objects. The following sources are installed when Knative is installed:

$ kubectl api-resources --api-group='sources.knative.dev'

NAME SHORTNAMES APIGROUP NAMESPACED KIND

apiserversources sources.knative.dev true ApiServerSource

pingsources sources.knative.dev true PingSource

sinkbindings sources.knative.dev true SinkBinding

There are many more sources, e.g. a Kafka Source or a CouchDB Source, but they need to be installed separately. To get a basic understanding of Knative eventing, the PingSource is sufficient. It creates something comparable to a cron job on Linux that periodically emits a message.

The Source links to the Sink so it is best to define/deploy the Sink first. It is a simple Knative Service, the code snippets are all from the Red Hat Knative Tutorial:

apiVersion: serving.knative.dev/v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: eventinghello

spec:

template:

metadata:

name: eventinghello-v1

spec:

containers:

- image: quay.io/rhdevelopers/eventinghello:0.0.2

And this is the Source definition:

apiVersion: sources.knative.dev/v1alpha2

kind: PingSource

metadata:

name: eventinghello-ping-source

spec:

schedule: "*/2 * * * *"

jsonData: '{"key": "every 2 mins"}'

sink:

ref:

apiVersion: serving.knative.dev/v1

kind: Service

name: eventinghello

- PingSource is one of the default Knative Sources.

- The Schedule is typical cron, it defines that the “ping” happens every 2 minutes.

- jsonData is the (fixed) message that is transmitted.

- sink defines the Knative Service that the Source connects to: eventinghello.

When both elements are deployed we can see that an eventinghello pod is started every two minutes, in its log we can see the message ‘{“key”: “every 2 mins”}’. The pod itself terminates after about 60 to 70 seconds (Knative scale to zero) and another pod is started after the 2 minutes interval of the PingSource are over and the next message is sent.

To recap the Source-to-Sink pattern: it connects an event source with an event sink in a one-to-one relation. In my opinion it is a starting point to understand Knative Eventing terminology but it would be an incredible waste of resources if this were the only available pattern. The next pattern is:

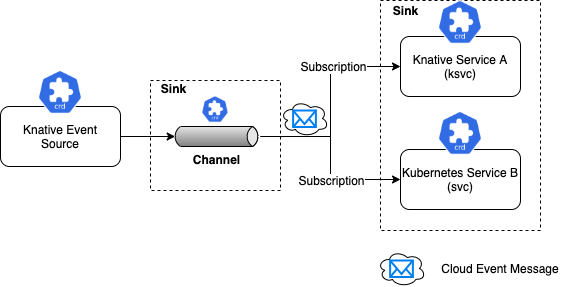

Channel and Subscription

A Knative Channel is a custom resource that can persist events and allows to forward events to multiple destinations (via subscriptions). There are multiple channel implementations: InMemoryChannel, KafkaChannel, NATS Channel, etc.

By default all Knative Channels in a Kubernetes cluster use the InMemoryChannel implementation. The Knative documentation describes InMemoryChannels as “a best effort Channel. They should NOT be used in Production. They are useful for development.” Characteristics are:

- No Persistence: When a Pod goes down, messages go with it.

- No Ordering Guarantee: There is nothing enforcing an ordering, so two messages that arrive at the same time may go to subscribers in any order. Different downstream subscribers may see different orders.

- No Redelivery Attempts: When a subscriber rejects a message, there is no attempts to retry sending it.

- Dead Letter Sink: When a subscriber rejects a message, this message is sent to the dead letter sink, if present, otherwise it is dropped.

A lot of restrictions but it is much easier to set up compared to the KafkaChannel where you need to create a Kafka Server first.

Knative Eventing is very configurable here: you can change the cluster wide Channel default and you can change the Channel implementation per namespace. For example you can keep InMemoryChannel as the cluster default but use KafkaChannel in one or two projects (namespaces) with much higher requirements for availability and message delivery.

A Knative Subscription connects (= subscribes) a Sink service to a Channel. Each Sink service needs its own Subscription to a Channel.

Coming from the Source to Sink pattern in the previous section, the Source to Sink relation is now replaced with a Source to Channel relation. One or multiple Sink services subscribe to the Channel:

(c) Red Hat, Inc.

(c) Red Hat, Inc.

The Channel and Subscription pattern decouples the event producer (Source) from the event consumer (Sink) and allows for a one to many relation between Source and Sink. Every message / event emitted by the Source is forwarded to one or many Sinks that are subscribed to the Channel.

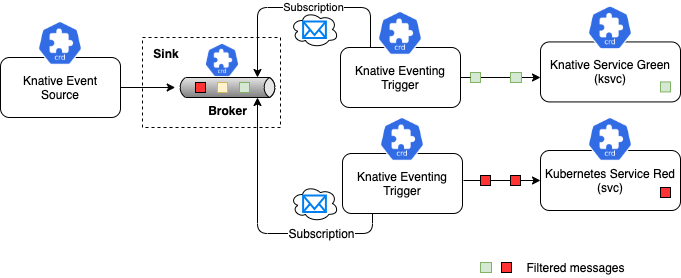

Brokers and Triggers

The Broker and Trigger pattern extends the Channel and Subscription pattern and is the most interesting scenario. Therefore I won’t go into more detail here but the Red Hat Knative Tutorial has an example for Channel and Subscriber.

A Broker is a Knative custom resource that is composed of at least two distinct objects, an ingress and a filter. Events are sent to the Broker ingress, the filter strips all metadata from the event data that is not part of the CloudEvent. Brokers typically use Knative Channels to deliver the events.

This is the definition of a Knative Broker:

apiVersion: eventing.knative.dev/v1beta1

kind: Broker

metadata:

name: default

spec:

# Configuration specific to this broker.

config:

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

name: config-br-default-channel

namespace: knative-eventing

A Trigger is very similar to a Subscription, it subscribes to events from a specific Broker but the most interesting aspect is that it allows filtering on specific events based on their CloudEvent attributes:

apiVersion: eventing.knative.dev/v1beta1

kind: Trigger

metadata:

name: my-service-trigger

spec:

broker: default

filter:

attributes:

type: dev.knative.foo.bar

myextension: my-extension-value

subscriber:

ref:

apiVersion: serving.knative.dev/v1

kind: Service

name: my-service

I think this is were Knative Eventing gets interesting. Why would you install an overhead of resources (called Knative Eventing) into your Kubernetes cluster to simply send a message / event from one pod to another? But with an event broker that receives a multitude of different events and triggers that filter out a specific event and route that to a specific (micro) service I can see an advantage.

(c) Red Hat, Inc.

(c) Red Hat, Inc.

This is the slightly modified example from the Red Hat Knative Tutorial:

To create a default broker requires no YAML. To use the default Broker for a Kubernetes namespace just add a label:

$ kubectl label namespace knativetutorial knative-eventing-injection=enabled

This will automatically create the required resources. To check:

$ kubectl get broker

NAME READY REASON URL AGE

default True http://default-broker.knativetutorial.svc.cluster.local 3d19h

$ kubectl get channel

NAME READY REASON URL AGE

inmemorychannel.messaging.knative.dev/default-kne-trigger True http://default-kne-trigger-kn-channel.knativetutorial.svc.cluster.local 3d19h

The first command shows the “default” broker is ready and listens to the URL http://default-broker.knativetutorial.svc.cluster.local. The second command shows that our default broker uses the InMemoryChannel implementation.

The example implements 2 services (sinks) to receive events: eventingaloha and eventingbonjour.

aloha-sink.yaml:

apiVersion: serving.knative.dev/v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: eventingaloha

spec:

template:

metadata:

name: eventingaloha-v1

annotations:

autoscaling.knative.dev/target: "1"

spec:

containers:

- image: quay.io/rhdevelopers/eventinghello:0.0.2

bonjour-sink.yaml:

apiVersion: serving.knative.dev/v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: eventingbonjour

spec:

template:

metadata:

name: eventingbonjour-v1

annotations:

autoscaling.knative.dev/target: "1"

spec:

containers:

- image: quay.io/rhdevelopers/eventinghello:0.0.2

They are exactly the same, they are based on the same container image, only the name is different. The name will help to distinguish which service received an event.

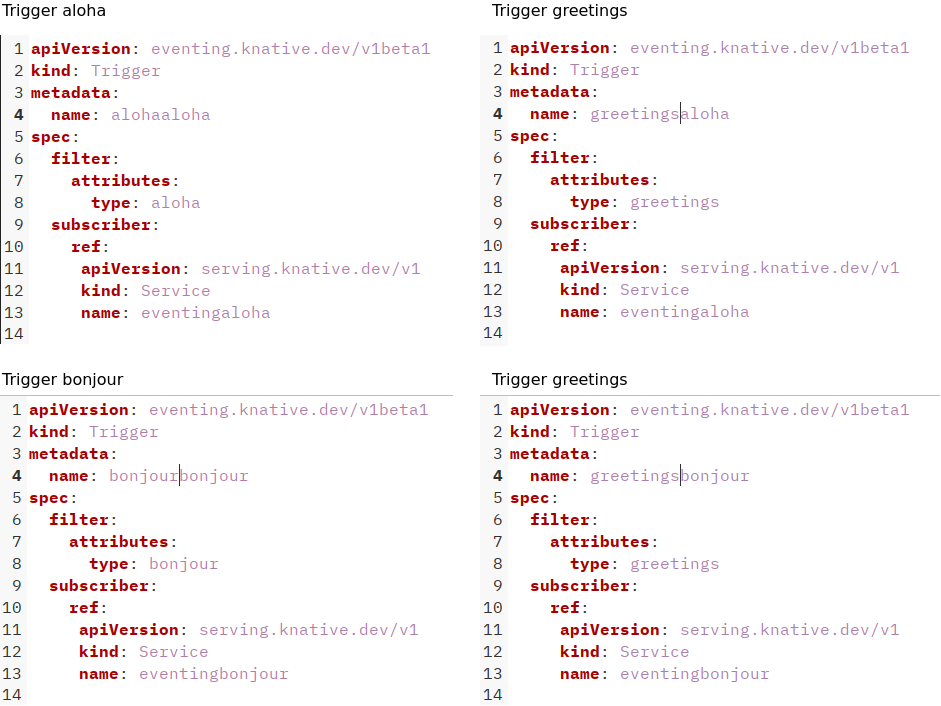

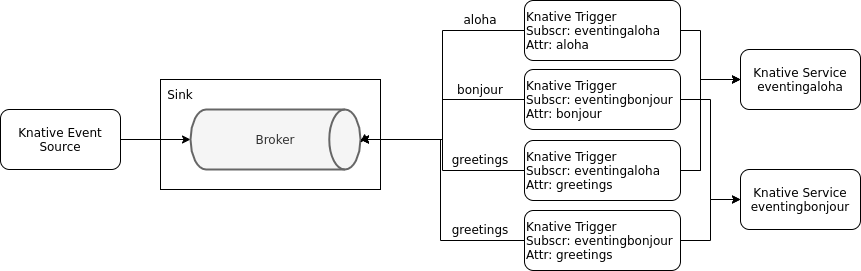

When everything is set up, we will send three different event types to the broker: ‘aloha’, ‘bonjour’, and ‘greetings’. The ‘aloha’ type should go to the eventingaloha service, ‘bonjour’ to the eventingbonjour service, and ‘greetings’ to both. To accomplish this we need triggers.

Triggers have some limitations. First, you can filter on multiple attributes, e.g.:

filter:

attributes:

type: dev.knative.foo.bar

myextension: my-extension-value

But the attributes are always AND: ‘dev.knative.foo.bar’ AND ‘my-extension-value’. We cannot define a trigger that would filter on ‘aloha’ OR ‘greetings’. We need 2 triggers for that.

Also a trigger can only define a single subscriber (service). We cannot define a trigger for ‘greetings’ with both the eventingaloha service and the eventingbonjour service as subscribers.

This means we will need 4 Trigger configurations:

If you start to seriously work with Knative Triggers, think about a good naming convention for them first. Otherwise troubleshooting could be difficult in case the triggers don’t work as expected: OpenShift Web Console does a very good job at visualizing Knative objects but it ignores Triggers. And this is what you see in the command line:

$ kubectl get trigger

NAME READY REASON BROKER SUBSCRIBER_URI AGE

alohaaloha True default 21h

bonjourbonjour True default 21h

greetingsaloha True default 21h

greetingsbonjour True default 21h

Our example now looks like this:

We have the Knative default Broker, 4 Knative Triggers that filter on specific event attributes and pass the events to one or both of the 2 Knative eventing services. We don’t have an event source yet.

A little further up we saw that the broker listens to the URL

http://default-broker.knativetutorial.svc.cluster.local

We will now simply start a pod in our cluster based on a base Fedora image that contains the curl command based on this curler.yaml:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

labels:

run: curler

name: curler

spec:

containers:

- name: curler

image: fedora:29

tty: true

Start with:

$ kubectl -n knativetutorial apply -f curler.yaml

Get a bash shell in the running pod:

$ kubectl -n knativetutorial exec -it curler -- /bin/bash

In the curler pod, we send an event using curl to the broker URL, event type ‘aloha’:

[root@curler /]# curl -v "http://default-broker.knativetutorial.svc.cluster.local"

> -X POST

> -H "Ce-Id: say-hello"

> -H "Ce-Specversion: 1.0"

> -H "Ce-Type: aloha"

> -H "Ce-Source: mycurl"

> -H "Content-Type: application/json"

> -d '{"key":"from a curl"}'

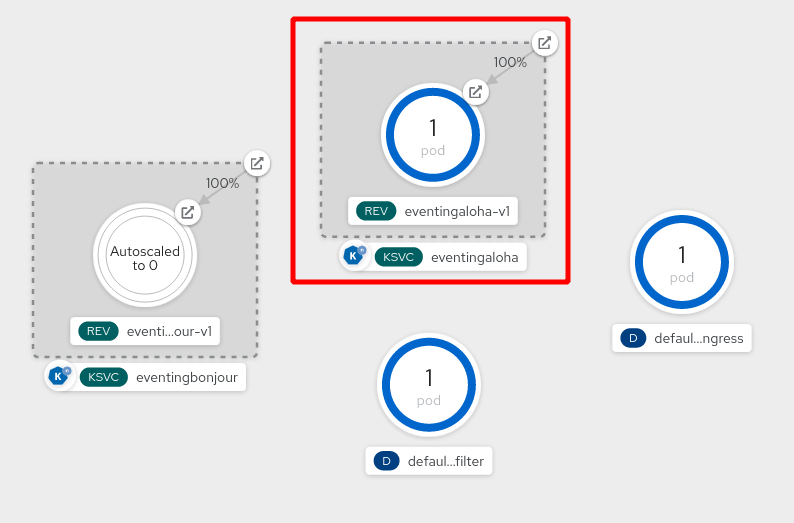

In the OpenShift Web Console we can see that an eventingaloha pod has been started:

After about a minute this scales down to 0 again. Next test is type ‘bonjour’, again in the curler pod:

[root@curler /]# curl -v "http://default-broker.knativetutorial.svc.cluster.local"

-X POST

-H "Ce-Id: say-hello"

-H "Ce-Specversion: 1.0"

-H "Ce-Type: bonjour"

-H "Ce-Source: mycurl"

-H "Content-Type: application/json"

-d '{"key":"from a curl"}'

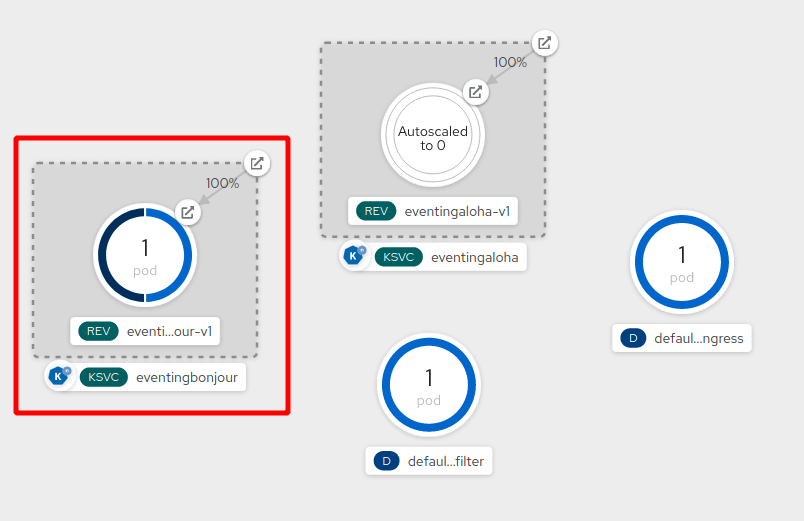

This starts a eventingbonjour pod as expected:

If we are fast enough we can check its logs and see our event has been forwarded:

2020-06-09 08:38:22,348 INFO eventing-hello ce-id=say-hello

2020-06-09 08:38:22,349 INFO eventing-hello ce-source=mycurl

2020-06-09 08:38:22,350 INFO eventing-hello ce-specversion=1.0

2020-06-09 08:38:22,351 INFO eventing-hello ce-time=2020-06-09T08:38:12.512544667Z

2020-06-09 08:38:22,351 INFO eventing-hello ce-type=bonjour

2020-06-09 08:38:22,352 INFO eventing-hello content-type=application/json

2020-06-09 08:38:22,355 INFO eventing-hello content-length=21

2020-06-09 08:38:22,356 INFO eventing-hello POST:{"key":"from a curl"}

In the last test we send the ‘greetings’ type event:

[root@curler /]# curl -v "http://default-broker.knativetutorial.svc.cluster.local"

-X POST

-H "Ce-Id: say-hello"

-H "Ce-Specversion: 1.0"

-H "Ce-Type: greetings"

-H "Ce-Source: mycurl"

-H "Content-Type: applicatio

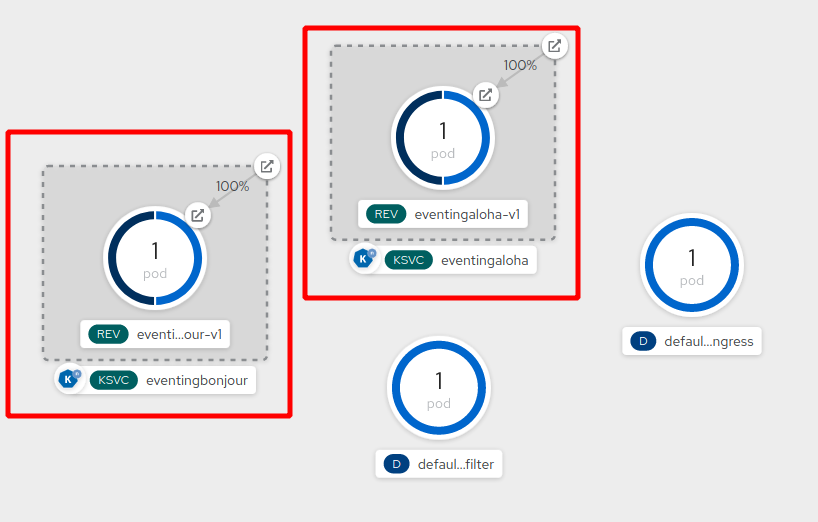

And as expected we see pods in both services are started:

Using Apache Kafka

I didn’t go through the Knative Kafka Example. But since it is hard to find and also the preferable method of setting up a production scale Broker & Trigger pattern for Knative Eventing, I wanted to have it documented here.

There are actually 2 parts in the Kafka example:

-

Start with Installing Apache Kafka: This will probably work in OpenShift (and CRC), too. But depending on the OpenShift version I would start to install the Strimzi or the Red Hat AMQ Streams operator from the OperatorHub catalog in the OpenShift Web Console and create a Kafka cluster with the help of the installed operator.

-

Continue with the Apache Channel Example. This example installs a Kafka Channel and uses it together with the Knative Default Broker. In the end, an Event Sink is created, a Trigger that connects the Sink to the Broker, and an Event Source (that uses the Kubernetes API Server to generate events).

Knative Eventing Recap

I have had a look now at both Knative Serving and Knative Eventing:

I really like Knative Serving, I think it can help a developer be more productive.

I am undecided about Eventing, though. The Broker & Trigger example based on the InMemoryChannel is easy to set up. But using the InMemoryChannel is for testing and learning only, it is not viable for production. And if I set up my cluster with an instance of Apache Kafka I do ask myself why I should take the messaging detour through Eventing and not use Kafka Messaging in my code directly.